#16: Turning Points

(Last time, Charlie and the rest of the gang were picking up the pieces of memory at Marnie’s house.)

Marnie had said I should call my parents. It was long distance, but she was right that I should check in. So I called early the next morning. They always woke with the sun.

“Charlie”—my mother like a burst of sunlight when she recognized my voice—“how have you been?”

“Fine, mom, fine.” I could hear the clamor in the background as my dad realized who was on the phone. I explained that I was at Marnie’s.

“Great, tiger.” My dad must have gotten on the phone in my parents’ bedroom. “How was the Appalachian Trail?”

“Have you been eating? I was telling Pops the other day how thin you looked.”

“Yes, Mom, I have been eating.”

She pressed, “And you had a good time hiking? How far did you get?”

I swallowed. “We didn’t get that far at all. We—we didn’t really go.”

“Oh?”

“Really?”

I swallowed again. “Yeah, we, um, actually ended up going to Kentucky for this, ah, wedding.”

My parents both started to talk so quickly that I couldn’t make out their words.

“It’s—it’s a long story.”

“Is this about some girl?” my mother asked.

Suddenly, my mouth felt very dry. “What?”

“Is this about some girl?”

“Mom, why would you ask that?”

She chuckled, like when my brothers or I feigned confusion about why a lamp was broken or why mud ran in tracks around our house. “When you go that far out of your way, a girl is almost always involved.”

Now it was my dad’s turn to laugh. “And the fact that you didn’t want to answer it—well, son, that’s like a bright red arrow that there’s some hanky panky going on in with you and, well, uh, this girl here.”

“Dad—I wouldn’t say it’s hanky panky. We’re uh…it’s just ah…”

“You go and do it. Live. You’re young. It’s good to see you getting out there, mixing it up with the honeys.”

“Frank…”

“I’m just trying to give the boy some encouragement, Luce. It’s not like when you and me were kids.”

“Mom—Dad—I’m running up Marnie’s bill here. I gotta go.”

“I wanna hear more about this,” my mother said as I pulled the phone away from my ear.

“Me, too.”

I hung up the phone, ripples of fire spreading through my cheeks.

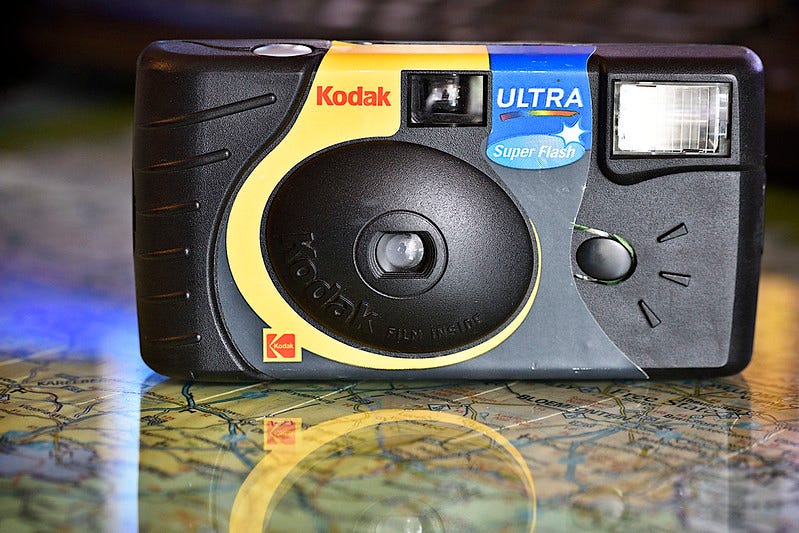

Pat chortled about the whole conversation on our way to the mall to get his disposable camera developed. “Hanky panky,” he hooted. Of course, he had heard me say that.

“I felt like I was twelve or thirteen again,” I said.

“Well, that’s not the worst thing in the world.”

I wondered why my parents would have said if I had told them about going out to Seattle to see Gina. You have to move on had been my mother’s mantra over the past year. Would she see that as a retreat to the past?

I don’t know what we did to each other back then, Gina had written. She was right. We had done so much to each other that it was hard to sort out: We had crashed the edges of our lives together, and sparks had erupted. It’s hard to have the light of sparks without the heat. We had helped remake each other.

As we drove past the crumbling façade of an abandoned factory, I thought that, yes, it would be nice to see Gina again. Even just to try to sort it out: to have some reckoning of where we had been and maybe even where we were now. Maybe we had grown up enough. Maybe I had grown up enough. That nagging hesitation in my brain—wasn’t that my infatuation with paralysis? Wasn’t it me losing myself in the coiling labyrinth of the saudade? I had mourned my relationship with Gina for over a year, and now—when it seemed like the coffin could rumble and rattle in front of me with some new life—why was I so reluctant?

We walked through the white halls of the mall as we waited for the film to be processed. Because it was early in the afternoon, the milling shoppers mostly had white or dyed hair. We each got a pretzel from a chain that had not yet spread to Massachusetts, but the pretzel tasted about the same as the ones from the chain at the mall back home.

“What do you think about Seattle?” I said as we walked away from the food court. Just like at almost every other mall I had ever visited, the Chinese food place had a guy out front holding a tray full of scraps of chicken, each pierced by a toothpick like a barren flagpole.

Pat chewed his pretzel for a few moments. “If that’s something you’re thinking about…”

“You don’t sound super-enthusiastic.”

“Charlie, it’s your life, and I back you no matter what. But are you ready to become her project again?”

“Pat—”

“I’m just saying—I’m just saying, are you ready?”

At last, the packet of memories was returned to us. Pat ripped the tape off the envelope of the pictures and began speeding through them. “It came out!” he cried. “Look, you can just see her face!”

Yes, Amelie Darfani’s face was at the edge of the picture, as she waved open-handed to the MTV crowd.

The past week was distilled into twenty-seven images. There were the tree-covered heights of the Adirondacks. The frozen ripples of metamorphic rocks. Ralph, Danny, and I hunched around the fire in Pennsylvania. A pickup truck with a Confederate flag fluttering from a pole on its bed. Danny asleep, with drool stretching down his cheek. The front of Mr. Smee’s TV and VCR Repair shop (“Don’t know why I took that one,” Pat said with a squint). An Iowa corn field drenched in rain.

Later that afternoon, I returned to the pictures spread out like playing cards on the table. My hand dropped down. The wedding. Here we all were. My smile was almost as wide as Bonnie’s. She looked so good in that dress. There were our faces stained with barbecue. Pat or someone had taken a picture of us dancing. A slight blur covered our limbs as we copied the dance scene from Pulp Fiction. I pulled my fingers in arrows over my eyes; she gripped her nose like she dropping under the water. And then I had copied that move. We had both seemed so playful and free there. The serious set of my lips was actually a joke. I could even see the arching corners of a smile. And she was grinning outright.

“You look happy,” Danny said from behind me.

“Yeah, I guess we were.” I picked up that picture and looked closer at it. “Pat said that same thing—that I looked happy then.”

“It still could be true, you know.”

I smiled. “Maybe. So how was lunch with Marnie?”

“They have a strange idea about what makes a ruben out here. No sauerkraut.”

“Positively barbaric.”

“Then Marnie said she had to go run some errands. Alone. I thought we were supposed to hang out today.”

“Must be a secret mission.”

Danny was right—I did look happy there. But was that the artifice of the camera, like the glowing eyes and the transfigured colors of the flash?

Pat insisted on making dinner that night. “A little token of thanks, Marnie.” He tightened the strings of the frilly gingham apron around his waist. “Time for the grillmeister.”

“Is that thanks—or a threat?” I asked. The minigrill that Pat had stowed on his porch in college had birthed more hockey pucks than edible hamburgers.

The spatula flew to his chest in a pose of mock offense. “Charlie, I’ve improved my technique, you’ll see.”

And the hamburgers were, well, hamburgers. The corn was delicious. “If it’s one thing we know how to grow in Iowa,” Jason said, “it’s corn.”

After dinner, Marnie brought out a small package wrapped in green paper. “I have a surprise.”

Instinctively, we looked at Jason, who shrugged.

“It’s a surprise,” she repeated. She dropped the package in front of Jason. “For you.” Her voice seemed brittle, for some reason.

Jason’s eyes swung between her and the box. “You want me to open this now?”

“Uh huh.”

Warily—like he was trying to defuse a bomb—Jason detached the tape from the sides and unfolded the paper. He carefully pulled off the top of the white box inside. He picked up a small bib with a squint.

“Babe, what is this?”

“It’s not babe,” she said, with tears trembling sapphires in her eyes. “It’s baby.”

“Baby?” He blinked. “Baby!” He sprung up to hug her. They kissed. And hugged. And kissed again. And hugged again.

It took a moment before the blastwave hit the rest of us. Wait—they’re having a baby! Someone I actually knew—a peer, not an adult or old person—was going to have a baby!? We started to applaud—to hoot—to holler.

“A baby!” Jason’s tongue still seemed to be wrestling with alien syllables. “How—how did this happen?”

“I think you know,” she replied to another explosion of laughter.

We congratulated and hugged them both.

And I went to hug Danny, too. “Congratulations, Uncle Danny.”

He answered with a blush.

Mello Drama

“Are you smoking pot in my sister’s backyard?”

He had found Ralph in a lawnchair. He had arranged three citronella candles in an equilateral triangle around his body. A crumpled white cylinder was pressed to his lips. He stank. He also looked a little guilty.

“I didn’t know you were back,” Ralph murmured.

“Ralph—in her yard?”

Ralph’s lids sunk closed. “I didn’t want to smoke in the house.”

“But I don’t know why you had to smoke at all.”

“You’ve ah—you’ve ah never gotten high, have you?”

“No.” The idea of it was repulsive. He shouldn’t have been so annoyed. But he was.

“It’s weird—they talk about getting high. But really it’s like getting low. You just slip into the grass and let the whole world go by. Life. Life is just so crushing.”

“That sounds depressing.” He didn’t add that it also didn’t sound true. He had to hold himself back.

“Everyone’s looking for an escape,” Ralph exhaled. “Some people are just more honest about it. What do you think nostalgia is about, anyway?”