#1: Setting Out

“Do you taste what I taste, Charlie?”

“No,” I said. “What?”

Beneath his dark sunglasses, Pat’s lips arched in a coyote’s grin. “Summer. Youth. Freedom.”

I tasted only a spoonful of dust.

I had grown a stranger to the morning sun. I would come back from work at night and stare at the TV screen or flip through my mom’s home-decor magazines or listen to the limping harmonies of late-night soft-rock radio. This is Daniel Adam Butcher with Bedtime Beats…Anything—anything—to defer sleep’s horizon of oblivion. Then, once I was in bed, leaving it seemed impossible. The crack in my heart made trench warfare out of every day. I would lie in bed, bound by the sheets that had grown heavy with the sweat and grime of so many churning nights. I would hear life beyond the solid wall—life so full, so sharp, so bright that I almost winced at the muffled words. I would want to leap out of bed and cross that threshold, my arms thrown open in exultation. I would feel so close—my fingers brushing the cool of the brass doorknob—but my head would not lift from the pillow.

But today here I was in Pat’s battered blue station wagon. I usually spent my nights drowning in the citrus fumes of toilet-bowl cleaners and wandering along the beach, watching the waves writhe upon the sand. Now, I would see the stars from another angle. In the Adirondacks, where we had a date with a mountain peak. In Iowa, where Danny’s sister lived. In San Francisco, where a giant bridge stretched over shimmering water. In Postultimate, Montana, where Mickey Kent’s temple of nostalgia ruled the plains.

Pat continued, “Can you imagine it! We’ve always talked about doing a road trip.” Pat had always talked about doing a road trip. “We’ve always wanted to see Kentstock.” Pat, a platinum preferred member of the Mickey Kent Fan Club, had always fantasized about going. “And now, we are!”

Mickey Kent was the reason—or at least the pretense—for our trip. Born Milton Kantor in Queens, he had taken a new name and racked up ten gold records during the 1950s, 60s, and 70s. He had starred in a dozen films. His 1984 autobiography, I, Mickey, had topped the bestseller lists. And, in the mid-80s, he had started Kentstock. For each of the past thirteen years, he and other wrinkled pop legends from the 1950s and 60s had taken the stage in Postultimate, Montana for one July weekend to stand athwart musical history yelling, Hold your horses!

“We’re not there yet,” I said. Postultimate was over two thousand miles from the East Coast.

“But we’re on the road—that’s what matters. We’re gonna roadtrip like it’s 1999.”

Young at the hinge of the millennium, we were barely a year out of college, and Pat was ready to seize the opportunity of Y2K.

His foot smashed the gas pedal, and we raced down the open highway. Pat’s driving was sudden, fast, and aggressive. With any opening, he’d charge through. He’d rush as soon and as fast as he could. He’d slam the brakes at the last possible moment, the bumper nearly kissing the care ahead. Pat never let go of any chance, and turned difficulty into an opportunity. When a torn rotator cuff had pulled him off the baseball team in high school, he had run to be class president. In college, he spent more time at political confabs than in the classroom. He had learned how to kneecap spending bills and charm campaign donors as a beloved lieutenant to Mistah Speakah, the hawk-browed boss of the Massachusetts state house,.

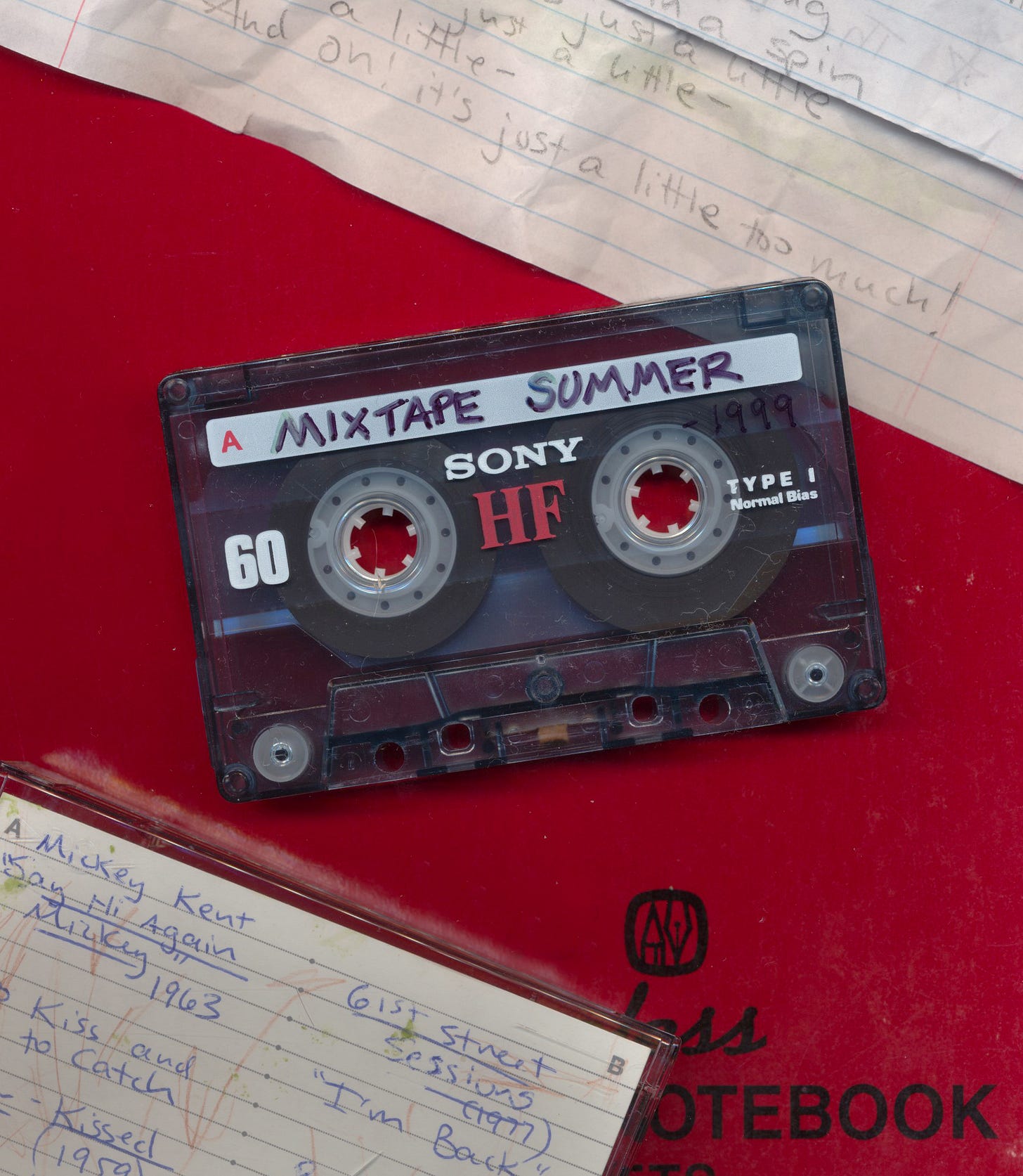

He lifted a stained cassette tape.

“Is that from high school?” I asked.

“You bet,” Pat said as he slipped it into the player.

“Any Mickey Kent on it?”

Pat didn’t need to answer. Mickey Kent’s songs were an intermittent soundtrack for our senior year of high school and could be found lurking in most of Pat’s mixtapes.

But it wasn’t Mickey Kent, at first. No, it was 2UpFront, with the swelling bass and percussive beats like record scratches.

Baby, I’m back Baby, I’m back Where we began. Baby, I’m back Where we all started. It was so fresh To hold your hand When we were fresh, And both open-hearted.

Was anything so sweet as being alive in those summer days, when hope was yet unbroken and joy was yet untarnished? When youth was not a fading dream and life was not an empty afterward?

How was it possible to feel so old at twenty-three? I didn’t know, but it was.

Saudade

My ancestors carried the saudade with them when they left for America from Cape Verde, that sprinkling of islands off the western coast of Africa. Saudade—the yearning heavy as lead and bright as gold, the desire for completeness in the face of loss, the longing for restoration. More than my father’s agate eyes or my mother’s ringlets—more even than my twisted back as a baby—the saudade was my birthright.

The saudade’s double helix of mourning and desire hints at the burden of memory. We remember the joys of before. We remember the pains of the past. The saudade conjures raptures and wonders, which distance makes only brighter.

The saudade tells of the sweet pain of yearning and the wonder of melancholy.

Once, I had floated charged with music.

Then, at twenty-two, my heart had cracked.

I pressed my face against the glass and watched the parade of the great democratic road. It was driven by presidents and CEOs and janitors and lawyers and circus-performers and movie stars and failed actors and store clerks and factory workers and accountants and policemen and preachers. The road promised so much—oceans, cornfields, malls, skyscrapers, slaughterhouses, zoos, canyons, mountains, forests, baseball fields, libraries, churches, synagogues, shrines, temples, amusement parks, hospitals, homes.

To look into the window of another car on the highway is to glimpse another life. A red-eyed man runs an electric razor over his face. Wearing furry costumes, two teenagers argue demonstratively, one waving an ape-like head in the air. A sun-burned couple in a car with “Just Married” written across the back window. Mystery coats those existential snapshots. Had that man slept late because he was camping out with his kids in the living room or because of another night-long assignation with a bottle of scotch? Were those kids pretending to be Bigfoot? What waited that couple in the years ahead—was their honeymoon just beginning or already ending?

We pulled alongside a red minivan, and a hook tugged at my brain when I saw the driver. About my age, she had brown hair that hung a little above her shoulders, kept back by a white-teared blue handkerchief. The sight of her freckled face shook the day the way wind revives a falling flag. Something about her made me wonder if I had been breathing when I first saw her. Maybe it was the handkerchief, or the teeth gleaming between her half-parted lips.

A great, irrational desire filled me—to call out to her—to unroll the window and wave and see if she would smile back. Our eyes would meet, and my hand would reach out the window, and—

And the pick-up truck in front of us drifted into the other lane. Pat accelerated. Whoosh. The scene was gone.

I didn’t know what to say to Pat. I certainly couldn’t talk about the fantasy of the highway—that bizarre coincidence, a random swelling in the chest. I wasn’t used to talking to people anymore. My parents were at work during the day, my brothers were away, and one of the perks of being a part-time janitor is that you get to work alone. By the time I’d get back to the house, everyone would be in bed. In many ways, that was a relief. I felt like a festering, walking wound in the house—a source of endless (but, luckily, silent) concern for my parents. From birth with my twisted spine, I was used to heavy looks. I had thought that I’d grown out of them, but, now, my cracked heart caused worry to pour like lead into the wrinkles around my parents’ eyes.

Pat always had something to say. For him, talking was like a reflex. If he took oxygen in, it had to come out in words. “You ever think about seeing Gina again?” he asked.

“What?”

“I mean, do you ever wonder what it would be like to talk to her again?”

“She moved to Seattle to get away from me, so I don’t think she plans on talking to me anytime soon.”

“Yeah yeah yeah. But if you were to, in some coincidence—”

“In some bizarre coincidence.”

“In some bizarre coincidence—what would you say?”

I sighed. “I’ve thought of that so many days.” And I didn’t know.

His mop of dark curls poking up at least a head higher than anyone nearby, Danny was waiting for us at the Braintree train station. As usual, he wore jeans and a dark t-shirt. The small pack on his back probably carried all his clothes; the duffel bag next to him was almost certainly full of textbooks, science-fiction paperbacks, lined notepads, and his laptop.

When Danny stuffed his duffel in the back of the station wagon (in between the tents, food supplies, and our bags), Pat said, “You forgot the other half of the library?” Pat once had boasted that the last book he read cover to cover was The Great Gatsby in eleventh grade.

“It’s just some catchup work for next semester,” Danny explained as he folded his figure into the backseat.

Pat squinted. “So let me get this straight, for the record: You’re trying to catch up for the future?”

“I think that’s the best way to catch up,” Danny said.

“I thought this was supposed to be a vacation, Danny-boy!”

“Well, there’s still a thing called being responsible.”

When I first met Danny in sixth grade, he was the tallest person in class and already showed a fantastic discipline—one that patience and drive. As he cut open the belly of our frog, the scalpel in his big hand did not waver a millimeter. College and, now, graduate school in chemistry had only polished that sense of care.

I had been surprised at first that Danny was willing to go on this voyage. As far as I knew, he didn’t really care about Mickey Kent. He hated to leave his work in Cambridge for a long weekend, let alone two weeks. One night, I suddenly understood. He had called to talk out the various routes he had planned for the trip (the highlighted maps were probably in that duffel bag, too). Near the end, he had mumbled, “This is going to be so fun.” Maybe fun had pulled him along, too.

“It looks like we’re right on time,” Danny said. “At this rate, we should get to Ralph’s place before dinner, just like we planned.”

“Pat might get us there faster,” I said.

“Just watch me, boys,” Pat cried, and the engine roared.

The Promise

With Gina, I went swimming in the deep end, where my feet could no longer touch the bottom. And eventually, I drowned.

Scene: College chemistry class, early in the morning. An empty lecture hall—except for her, flicking through an issue of Wired. I sat a few rows behind her, and she said, “Well, that’s friendly.”

“Oh,” I said. “I didn’t want to disturb you.”

She turned her head, and a glance like a throwing knife sliced through the air. “Am I that scary?”

So I got up and sat next to her.

She was all bones and edges. Her jaw had a boomerang’s sharpness. When she wore super-short jean shorts, her knees stood out like little peaks. Thin silver bracelets jangled on her bony wrists. Her moods balanced on a dagger’s edge. I’d say a joke one day, and she’d rebuke me: “Don’t try too hard, Charlie. It makes you look like a tool.” Another joke another day, and her laughter ran over me with a million tickling fingers. Usually, she’d save a seat for me in class or wait for me to sit down. But sometimes, she wouldn’t. I never knew how each day would go. It was thrilling. As the professor lectured on covalent bonds, I spent more time staring at her long black hair and smooth, tanned legs than I did at the blackboard.

When I asked her to go to see That Thing You Do!, she just said, “I was wondering when you’d ask me out.”

As I put my arm around her shoulders at the movies, I wondered if she could feel the stomping in my veins. After, we wandered the Public Gardens in the heart of Boston. We passed the flowers—archipelagos of color—and walked by the scattered fountains. “I love the Gardens!” Gina exclaimed. The wind picked up. Flame-gold leaves swirled through the air, as though the sky were afire. I gave into the wind. When our lips met, I wrestled with peach-tinted lightning.

Our first stop was a county fair in Central Massachusetts. A state senator who was one of Mistah Speakah’s closest allies had set up a booth, and Pat had been tasked with delivering a couple cartons of pamphlets and party literature to that democratic outpost.

“Ready to spread the good news?” Pat asked as he pushed a heavy cardboard box into my hands.

While Pat was gaming out what he called Al Gore’s “can’t fail” path to victory in next year’s presidential election, I started walking toward the entrance to the fair. I had already heard Pat lay out this strategy many times before. Repetition did not make it more interesting.

And then my view crashed into a car.

“It’s impossible,” I murmured. But it was the same color. And it had had that Grateful Dead bear bumper sticker, right?

“What is it, Charlie?” Danny called.

Was there anything else I could remember about that minivan? Some ding on the door like a fingerprint?

“It’s nothing,” I said. “I just think I saw this car on the road earlier. It’s weird.”

“Weird—not nothing,” Pat countered.

“Well, it’s just a coincidence,” Danny said.

“It is? Charlie, what caused you to notice this car in the first place?”

I could feel Pat’s psychic fingers poking at the surface of my brain, testing every fold. He had a sixth sense for weakness—and folly. He almost certainly knew what I was going to say, so there was no point in trying to dodge. “Because of who was driving. A girl.”

“See, Danny?”

“Actually, I don’t see.”

“I think we’re going to have to keep our eyes peeled. Charlie, what does this feminine phantom look like?”

Trying to describe her made me realize how little I knew, just a constellation of features: bandana, freckles, a distant gaze. I knew I would know her again if I saw her—but could not paint her with words.

“Sir, sir,” a guard sputtered as we approached the gate.

Grinning, Pat kept walking—maybe even a little faster. “We’re just here to deliver some materials to Senator McNeil. That’s all.”

That’s how Pat was: smile and keep going. And, somehow, the universe consented to that. He had a way of molding life to his will. The guard just shrugged and waved us by.

The notes of some twangy band spun in the distance. High schoolers and middle schoolers swarmed around us in packs—the limbs of boys and girls languorously intertwined. A flannel-topped Goliath in overalls walked past pushing a pallet stacked with chicken cages. I almost stumbled into a man in an oversized sleeveless t-shirt with the slogan: “Nothing to Lose, Nothing to Fear.” A pink fanny pack wrapped around her waist, the woman with him glared at me.

“Sorry, sorry,” I said. Somehow, the universe did not always conform to me with such velvet ease.

When Pat was with his fellow political operators, everything about him sharpened—a razor’s edge even glinted in his laughter. I peered through the crowd of teenagers and families and electric beeps and striped tent-tops and rides whirling in the horizon. I always liked the idea of fairs. Going into some place where the rules didn’t apply, where endless amusement waited and the burdens of life were lifted, had a glistening appeal. But experience had rarely lived up to that promise. Long lines, five-dollar sodas, and rigged games drained glamour from the scene. Dreams commercialized soon lose their allure.

“And now,” Pat said, “we’re on the hunt.”

“For what?” Danny asked.

“For Charlie’s vision of the highway, what else?”

Pat swept off, and Danny followed in his wake. “Pat, we can’t spend long here. We’ve got a schedule to keep, and Ralph’s expecting us.”

Pat chuckled—still sharp. “You think PL will care if we’re an hour or ten late? He’s probably swimming in bong smoke already.” Sometime when they became roommates during college, Pat had given Ralph the title PL (for poet laureate).

“What’s the gameplan here, Pat?” I asked.

That caused him to spin to face me. “What’s the gameplan? I thought the gameplan was fun. So let’s go!”

“What if we find her?”

“I knew there was an optimist hidden somewhere in there, Charlie.”

“What do you mean?”

“I mean, that’s your first question—what happens if you get what you want?”

So I gave into the spirit of fun and joined the bizarre scavenger hunt for the face I had seen once on the highway. We slipped through the crowd, scanning scanning scanning. Pat held his hand to his ear like a Secret Service agent. His head poking up like a crane amidst the suburbs, Danny looked back and forth.

A purple bandana—not a blue one.

Girls raced screeching by in floral skirts.

We scattered around the rides, searching through the lines and the screaming faces on the Whirling Dervish.

“I found her, I found her.” Pat raced up to me.

He pulled me through the crowd. For some reason, the thrill of my pulse had accelerated.

It was a five-year-old dressed up like a cowgirl with—yes—a blue bandana around her neck.

“Very funny, Pat,” I said as we passed by her. Maybe it was the heat or hunger, but it did actually seem kind of silly, even fun.

We chased through a maze of mirrors. The wavering glass massaged my form—stretching, shrinking, squeezing. Laughter rose wild around me.

My friends and I looked and looked and looked. Nothing. Nothing. Nothing. How could she be seen in the crowd? We were like two dim candles in a fog. We could dance mandala-pirouettes around each other for days without touching. And what if she wasn’t even there? What if she had left? What if she had never been there at all?

“Well,” Pat said, “we tried.” We were all picking from a basket of tempura vegetables from one of the food-stands around the stage.

The music was familiar—was it Vivaldi? Whatever it was, I had heard it before, but it was changed. Everything seemed keener, the highs and lows more vertigo-inducing. The notes of the violin took some thin phantasm of memory out of my brain, and, with the dash of the bow, transformed it into something strange and charming.

I looked toward the stage and dropped the half-eaten piece of fried cauliflower.

It was her.

*

Thank you for reading Mixtape Summer! To see what happens next week, consider subscribing.

I love how you describe the lives inside the vehicles as they drive by!!!